Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Pulsars III

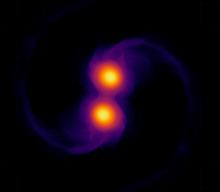

Scientists made big news last year when they announced the first detection of gravitational waves — ripples in space and time caused by the motions of massive objects. Even before the first discovery though, scientists had good evidence for the existence of the waves: measurements of the mutual orbit of two dead stars.

In 1974, two astronomers found a pair of neutron stars in orbit around each other. Neutron stars are the crushed cores of exploded stars. One of them in this binary system spins rapidly, emitting pulses of radio waves with each spin, so it’s known as a pulsar.

Precise timing of those pulses over the years revealed that the two stars are spiraling closer to each other by about 10 feet per year. That matches predictions in Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity. The theory says that massive objects should lose energy by emitting gravitational waves, causing them to get closer.

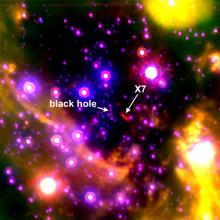

Today, astronomers are using pulsars to try to detect much longer waves — produced by supermassive black holes. Such black holes may spiral toward each other when two galaxies merge.

The gravitational waves from such an encounter would take years to pass through Earth. Each wave would compress and stretch space by a tiny amount. That would change the timing of the radio signals of pulsars. So by precisely measuring the “ticking” of many pulsars, it should be possible to catch the gravitational waves from black-hole monsters.

More about pulsars tomorrow.

Script by Damond Benningfield