Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

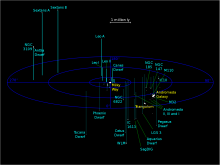

You are here

Winter Milky Way

Not many people seek out dark skies on cold winter nights — they’re not prime skywatching time for much of anyone. But those who do find dark skies get a treat: a nice display of the Milky Way. It arcs high overhead in early to mid evening right now. It’s anchored in the southeast by Sirius, the night sky’s brightest star. It then climbs high overhead to the “horns” of Taurus, then drops toward M-shaped Cassiopeia in the north, and the tail of Cygnus, the swan, in the northwest.

The winter Milky Way is thinner than that of summer. That’s because we’re looking away from the crowded center of the galaxy and toward its thinly settled rim. In fact, the point directly opposite the galaxy’s center is at the tip of one of the horns of Taurus, near a star called El Nath.

The rim is about 25,000 light-years away — about a quarter of the diameter of the Milky Way’s bright disk of stars.

But the galaxy doesn’t end there — there’s more stuff outside the disk than inside. Up to 90 percent of the Milky Way’s mass consists of dark matter — material that produces no detectable energy, but that exerts a gravitational pull on the visible matter around it. Most of the dark matter forms a “halo” around the disk — a region that extends hundreds of thousands of light-years into space.

So while the stars may disappear as you look beyond the Milky Way’s disk, the galaxy itself most certainly does not.

More about the Milky Way tomorrow.

Script by Damond Benningfield