Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Stellar Disruption

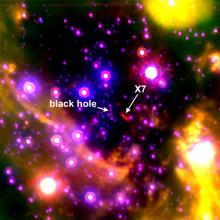

The problem with black holes is that they’re black — they don’t produce any detectable energy at all. So astronomers find and study black holes by observing their effects on the stuff around them. They pull at nearby stars, for example. And they sometimes “feed” on gas and dust, which glows brightly as it spirals toward a black hole.

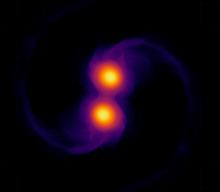

One of the most spectacular effects is when a black hole rips apart a star. Known as a tidal disruption event, it can be as bright as a supernova. It can shoot out bright “jets” of charged particles. And it can shine for years.

A star has to pass a black hole at just the right distance to be disrupted. If the star goes directly toward the black hole, it can be completely gobbled up, with fewer fireworks. Too far, and it gets away cleanly.

At just the right distance, though, the black hole rips the star into a blazing stream of hot gas. Much of the gas enters orbit around the black hole, blazing brightly before it’s devoured. The rest of it escapes the black hole, forming bright streamers that slowly cool and fade.

In the last decade or two, astronomers have seen perhaps several dozen of these events. Most of them have been produced by supermassive black holes. These monsters sit in the hearts of galaxies. They weigh millions or billions of times the mass of the Sun.

But an event reported this year appeared to be caused by a rare middle-weight black hole. More about that tomorrow.

Script by Damond Benningfield