Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Leonid Meteors

A quiet but steady meteor shower should be at its peak over the next night or two. And the gibbous Moon sets by around 1 or 2 a.m., so it won’t spoil the display. At its best, you might see a dozen or more “shooting stars” per hour.

The shower is known as the Leonids. That’s because its meteors appear to “rain” into the sky from Leo, the lion, which climbs into view in the wee hours of the morning.

There’s no relation between the meteors and the constellation, though. Instead, the meteors are the offspring of a comet.

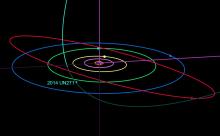

Comet Tempel-Tuttle was named for the two men who discovered it, in 1865. Not long after the discovery, several astronomers noted a correlation between the orbit of the comet and the Leonid meteor shower. They realized that the comet must somehow spawn the shower.

And they were right. A comet is a ball of frozen water and gases mixed with bits of rock and dirt. When it gets close to the Sun, some of the ice vaporizes, releasing solid particles. When Earth crosses the comet’s path, some of the particles ram into the atmosphere, forming the glowing streaks known as meteors.

The debris in the comet’s path is clumpy, though, so the meteors aren’t evenly distributed. Some experts say we could pass through several clumps over the next few nights, keeping the Leonids going for a while. So if you have a safe, dark viewing spot, it’s worth looking for the Leonid meteors — the offspring of a comet.

Script by Damond Benningfield