Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Sirius B

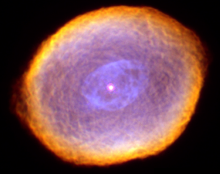

The Sun and similar stars are steadily losing weight — they blow some of their gas into space through strong “winds.” And at the end, they blow away all of their outer layers of gas, leaving only their hot, dense cores, known as white dwarfs — tiny remnants of once glorious stars.

An example is Sirius B, the companion to the Dog Star, Sirius A, the brightest star in the night sky. Sirius climbs into view in the east-southeast by around 8:30 or 9, and arcs across the south during the night.

Sirius B is too small and faint to see without a telescope. But millions of years ago, that wouldn’t have been the case. The star probably was a few times as massive as the Sun, so it would have shined brighter than Sirius A is today.

Such a hot, bright star produces a much thicker wind than the Sun does, so it loses mass at a higher rate. And because the star was heavier than the Sun, it burned through the nuclear fuel in its core much faster. As a result, it burned out in a couple of hundred million years, while the Sun is still only half way through a 10 billion-year lifetime.

As it neared the end of its life, Sirius B puffed up like a giant balloon, then expelled its outer layers. Some of that gas probably piled on the surface of Sirius A, increasing its mass.

Today, Sirius B is as heavy as the Sun, but only as big as Earth. It still shines because it’s extremely hot. But it’s only a faint remnant of its former glory.

Script by Damond Benningfield