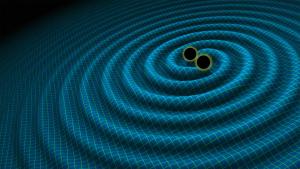

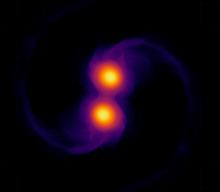

Two black holes produce gravitational waves as they orbit closer and closer to each other in this artist's concept. The black holes eventually will merge, producing an outburst of gravitational waves, which are ripples in space-time. Detectors on Earth have discovered the waves from several merging black-hole pairs, as well as a pair of merging neutron stars, confirming one prediction of Albert Einstein's theory of gravity. [NASA]

You are here

LIGO

A buzzing insect, a speeding locomotive, and a pair of merging black holes have something in common: They all produce gravitational waves. These “wiggles” in space-time are so puny, though, that only those produced by the black holes are detectable. In fact, by the end of last year, scientists had detected the waves from 10 black-hole mergers.

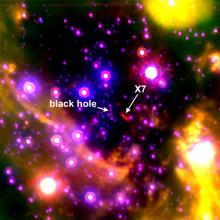

Those detections were made with LIGO — a pair of observatories in Louisiana and Washington state. And the last few detections were aided by an observatory in Europe.

Gravitational waves are produced by moving objects. They’re incredibly tiny, though, so they’re incredibly hard to find. It takes a massive object moving at extremely high speed to produce waves that are big enough to detect.

Each of LIGO’s detectors consists of mirrors placed at the ends of two vacuum chambers that are more than two miles long. A laser beam is split in two and reflects back and forth off the mirrors.

If a gravitational wave passes by, it compresses one of the arms by about one ten-thousandth the width of a proton. That’s enough to be recorded by sensitive detectors. The event must be “seen” by both LIGO sites to be considered a true detection.

Merging black holes are good targets because they’re small but heavy. And just before they merge, they’re moving at a good fraction of the speed of light. That whips up space-time, producing waves that are just big enough for LIGO to record.

More tomorrow.

Script by Damond Benningfield

Get Premium Audio

Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.