Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Lupus

A scraggly wolf pads low across the southern evening sky at this time of year. Lupus is to the lower right of Scorpius, the scorpion. Unlike Scorpius, though, you need a fairly dark sky to see it.

Even the wolf’s brightest star isn’t all that bright. And it’s so far south that you need to be south of about Dallas to see it at all.

Someday, Alpha Lupi will shine much brighter. That’s because the star is about 10 times the mass of the Sun. Such a heavy star is likely to end its life as a supernova — a titanic explosion. The star’s core will collapse to form a neutron star. Its outer layers will blast into space. For a few weeks or months, it’ll outshine billions of normal stars.

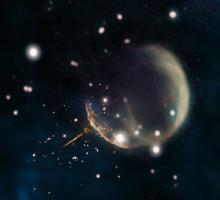

That’s already happened to another star in Lupus. It flared up a millennium ago. At its peak, it was several times brighter than Venus, which right now is the brilliant “morning star.” It was bright enough to see during the day, and at night it was bright enough to read by.

Supernova 1006 was different from the kind of supernova that Alpha Lupi will become, though. It probably formed from the merger of two dead stellar cores known as white dwarfs. Their combined mass was enough to spark a runaway nuclear explosion — like a giant H-bomb. It blasted the two stars to bits. Today, all that remains is a cloud of debris about 65 light-years across. It’s continuing to expand at about one percent of the speed of light — the most interesting feature of a scraggly wolf.

Script by Damond Benningfield