Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

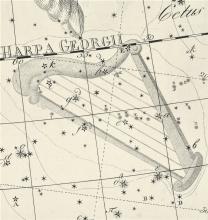

The Crane

When European sailors began exploring the southern hemisphere, they compiled maps of the stars. Astronomers used those maps to create some new constellations. And one of those constellations moves low across the south on November nights: Grus, the crane.

Grus was first featured on a celestial globe, in 1598. A few years later it was depicted in a famous star atlas, and it’s been around ever since.

The crane’s “head” and several other stars were taken from Piscis Austrinus, the southern fish. But the head retained its “fishy” name: Aldhanab, from a longer Arabic phrase that means “the tail of the fish.”

The star has passed the end of its “normal” lifetime, so it’s gotten much bigger and brighter. It’s more than four times wider than the Sun, and it emits almost four hundred times as much energy. It’s much hotter than the Sun, so most of its energy is in ultraviolet wavelengths, which are invisible to the eye.

Grus’s brightest star is Alnair — “bright one of the fish’s tail” — in the crane’s body. It, too, is at or near the end of its normal lifetime, so it’s also hundreds of times brighter than the Sun.

Grus hugs the southern horizon as night falls. From the northern half of the U.S., only its head and neck are visible. To see Alnair and the rest of the crane’s body, you need to be south of about Kansas City. And if you’re south of about Dallas, you can see its legs as well — the long legs of a celestial crane.

Script by Damond Benningfield