Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Faint Giant

Hercules is in his prime at this time of year. The strongman is well up in the eastern sky at nightfall, and stands high overhead in the wee hours of the morning. And as seems only proper, Hercules is a giant — only four constellations are bigger. It spans about 50 degrees both north to south and east to west — five times the width of your fist held at arm’s length.

Yet Hercules is also the faintest of the big constellations. Its brightest stars are only third magnitude. They’re easy to pick out under dark skies, but not so easy from a light-polluted city. And its fainter stars are completely blotted out by the glow from streetlamps, parking lots, billboards, and other artificial light sources.

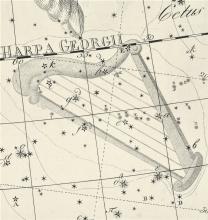

The constellation’s official outline is invisible, too — its official borders. They form a polygon made of 28 individual segments.

Astronomers began developing those borders 100 years ago this month. There were many constellations, but their arrangement was a little sloppy. Some constellations overlapped others, while some parts of the sky had no constellation at all. So the International Astronomical Union brought some order to the chaos. It got rid of quite a few constellations, and drew official borders for the 88 that remained. That created a night sky that’s like the patches on a quilt, with each patch connected to others. And it gave every star a constellation of its own — through a process that began a century ago.

Script by Damond Benningfield