Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Orionid Meteors

The surface of Comet Halley is being peeled away like the skin of an onion. It loses a layer about three to 10 feet thick every time it passes near the Sun. And that’s good news for skywatchers. Earth intercepts some of that debris every October, creating the Orionid meteor shower. The shower should be at its best the next couple of nights.

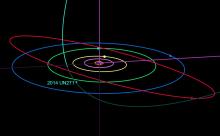

Halley is a slab of ice, rock, and dust that’s about nine miles long. It comes closest to the Sun every 75 years or so. The Sun warms the surface, vaporizing some of Halley’s frozen water and other ices. The vapor spews into space, carrying some of the rock and dirt along with it.

Over time, the material spreads out along the comet’s orbit, forming long, skinny clouds of debris. A new streamer forms with every close approach. Some of them are wider and thicker than others.

Earth intersects Halley’s orbit every October. Bits of comet dust slam into the upper atmosphere at almost 150,000 miles per hour. The debris quickly vaporizes, forming the streaks of light known as meteors.

The shower should be at its best tonight and tomorrow night, after midnight. Under clear, dark skies, you might see a dozen or more meteors per hour. If you trace their paths across the sky, all of them appear to “rain” into the atmosphere from Orion — hence the shower’s name. But the meteors can blaze across any part of the sky — the remnants of a slowly disappearing comet.

Script by Damond Benningfield