Listen to today's episode of StarDate on the web the same day it airs in high-quality streaming audio without any extra ads or announcements. Choose a $8 one-month pass, or listen every day for a year for just $30.

You are here

Moon, Jupiter, and Spica

The Moon is just past full this evening. Sunlight illuminates all but a sliver of the lunar hemisphere that faces our way, so the Moon is bright and beautiful. And it has a couple of bright, beautiful companions. The star Spica stands to its upper right, with the brilliant planet Jupiter above Spica.

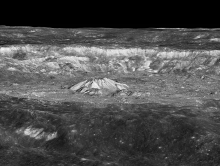

If you look at the Moon, you’ll see the same features that are always in view — dark volcanic plains and lighter-colored highland regions. They’re the same features you’ll see tomorrow night, and a month from now, and a hundred years from now.

Since the same side of the Moon always faces our way, you might think that the Moon doesn’t turn on its axis. But that’s not the case. In fact, if it didn’t turn we’d see the entire Moon — the familiar near side and the hidden far side. Instead, it’s the rate at which it turns that keeps it aiming our way.

Over the eons, Earth’s gravity created tides in the lunar surface. That slowed the Moon’s rotation. Eventually, it slowed enough that the same side always faces our way. So the Moon turns on its axis at the same rate at which it orbits Earth. By the time it’s moved a quarter of the way around us, it’s also completed a quarter turn on its axis, and so on.

The Moon, of course, creates tides in Earth’s oceans, which are slowing its rotation. So if Earth and Moon are around long enough, then just as the same hemisphere of the Moon always faces Earth, the same hemisphere of Earth will always face the Moon.

Script by Damond Benningfield